Charcoal

Something of interest to me is artist materials and the separation between the artist and their chosen medium; a distance lengthened by the digital age and the consumerism ingrained within modernity. The materiality of an artwork reflects this disconnection or reconnection to a medium and further, to its biological origin: plants. Chosen media serves as an artist’s connection to the material and natural world. After all, “plants remain ‘the primary mediators between the physical and biological world;’” (Niklas, pp. 86). For this endeavor I chose charcoal, since it is my primary and longest-standing medium. This aims to go beyond utility and the anthropocentric concept of resource value, but to more philosophical approaches based on our course concepts of plant blindness, symbolic registers, and anthropocentrism.

Part 1: Four Artists

Artist charcoal is carbonized wood from twigs of willow trees, grape vine, or hardwoods (from angiospermous tress) such as ash, beech, oak, hickory, and walnut "that have been heated at a high temperature in an enclosed vessel without oxygen” (“Charcoal”). Some artists also use other materials such as coconut shells or bamboo to create charcoal depending on their region (Kroeck). The powdery nature of charcoal requires paper or other drawing surfaces to be more textured and fibrous; often with visible or tactile signs of the plant fiber remaining (“Charcoal — Art Mediums”).

Like the class learned about indigo, charcoal is a medium that is closely tied to its plant’s characteristics and ecological history. Charcoal is an artist medium that has existed throughout the world for centuries, like indigo. Unlike indigo, however, it is a medium that was not preciously sought after for its color but widely spread for its affordability and ease of production as an artist medium. Depending on the type of wood used, the type of charcoal produced also differs. American willow and grape vine wood create a brittle charcoal easily erasable by the palm of your hand and the Korean white-bark pine tree “...radiates [a] light gray/blue ash color” (Anderson).

For this project, I wanted to research why artists choose charcoal over other mediums, their connection to the history of the material, and to assess the level of anthropocentrism present in their work. I have chosen to cite contemporary artists’ work including Tansy Lee Moir, Bahk Seon Ghi, Gustavo Nazareno, and Lee Bae.

Tansy Lee Moir

Tansy Lee Moir’s body of work solely depicts trees, relating the human figure, narrative, and emotion to detailed tree drawings (Carey). This is an anthropocentric approach to her symbolic register but her level of dedication to her subject and research into her subjects expresses the individuality of each tree both ecologically and aesthetically.

Bahk Seon Ghi

Bahk Seon Ghi is a Korean sculptural artist who works in suspending pieces of charcoal with clear nylon string, the house-like structures of his sculptures “challenges viewers to reconsider their connection to the natural world” (“Bahk Seon Ghi”). I was interested by his depiction of a houseplant (pictured above) and how its unexpected suspension in a gallery space asks viewers to reconsider their own connections to their houseplants and perhaps greater environment. He has a deep connection to the material of charcoal as a type of wood but there is not much connection to the nylon string except as an aesthetic decision for his artwork.

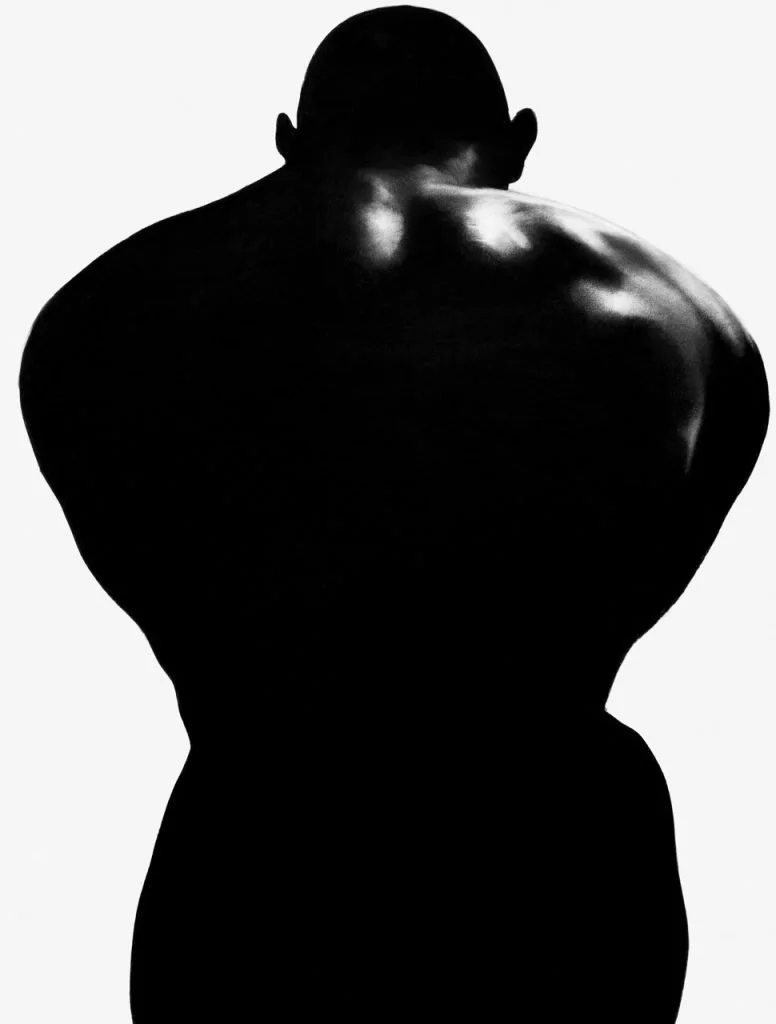

Gustavo Nazareno

Gustavo Nazareno is a Brazilian artist interested in creating oil paintings and charcoal drawings that embody a synthesis of the spiritual and cultural histories of Africa, Europe, and South America (“Discover the Works of Gustavo Nazareno”). Interestingly, his charcoal drawings of people and of animals and flowers share a similar weight of importance with the shared dramatic chiaroscuro. This is like the flat ontology we studied in Freud’s paintings, where humans are not visually more important than plants.

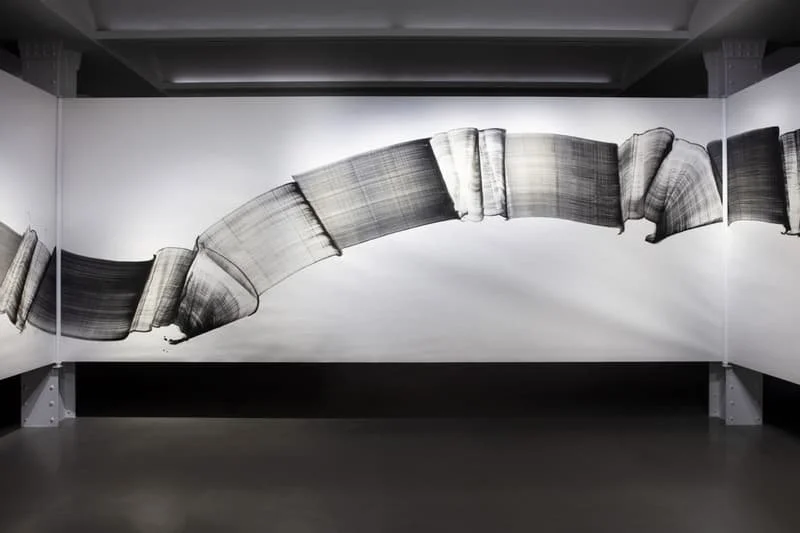

Lee Bae

Lee Bae is a world-renowned French Korean artist who creates his own charcoal. Though visually, Lee’s body of work is abstract, the expertise and cultural connection he has to his medium suggest a deeper representation of the Korean pine tree through his methodology. He expresses the “cyclical nature of life and death,” beyond purely humanist mentality but ecologically as well as he locally sources his wood in the town he resides, Cheongdo (Anderson).

Part 2: Making Charcoal

The following are resources I compiled for artists creating their own charcoal, including artists and educators such as Simon Seretse Attwood (a SAIC alum), Center for Art Education and Sustainability (CAES), Darren Rousar, and Susan Snipes. While researching the topic of charcoal artists and their connection with nature, I was intrigued by artists who create their own materials.

Part 3: Blog

Abscissions

Botanical Revolutions by Dr. Giovanni Aloi

Rachelle Lee

Welcome to my course blog!

Abscissions are parts of a plant that naturally fall off, like leaves and fruit.

My blog is titled this as a reference to my documentation of my course material falling like leaves that nourish the soil of my future academic pursuits. Here you will find weekly commentary of what I learned throughout this course. These are in blog post format with the most recent entries placed at the top.

Post 7: Case Studies

4/15/25

This was our last lecture together covering four “case studies” of artistic practices that implement key principles of our course content. These projects were presented as examples of reclaiming plant symbolism, environmental advocacy and the education of local ecology, confrontation of the histories of enslavement through plants such as kudzu and cotton, and the disruption of the purist traditions of the lawn to resurface native history. The projects and artists included today were as follows:

The Pansy Project (ongoing) by Paul Harfleet

Through the Eye of the Unicorn (2024) by Jenny Kendler and Giovanni Aloi

To See the Earth Before the End of the World (2022) by Precious Okoyomon

Grasslands (2014) by Linda Tegg

Final Project Update: Like most good courses, I have more questions than answers in the end. At this point in my research into charcoal and learning about critical plant studies, I wonder: do plants like artwork? Do plants yearn for immortality? Does the memory of a plant live on in an artwork made from it? Should it? Will a tree mind that I take some of its fallen twigs for charcoal? Will the forest?

Post 6: Tendrils

4/8/25

The lecture today was titled, “Tendrils.” Tendrils are the “slender spirally coiling sensitive organ” or the arm-like parts of a plant that reach out, exploring for stable structure to wrap itself around and hold onto (Merriam Webster). Aloi suggested that these tendrils are a sign of plant intelligence; the arms reaching out expressing a plant’s ability to remember, desire, and decide.

A project mentioned for class critique was by Spela Petric, entitled Pl’ai (pronounced play) where cucumber plants’ tendrils were stimulated by colorful plastic balls moving up and down using AI programming. We reached an uncharted area in the discussion when several students discussed the lack of signs of the plant’s enjoyment and desire, which pushed us further into the speculation that plants do have a preference beyond survival instincts.

As a plant for thought, Aloi introduced the Chicago dodder plant to us – a bright yellow, net-like plant that does not photosynthesize. The dodder has six days to find another plant to pierce its tendrils into for nutrients. Once it finds a plant, it searches for more, connecting multiple into a sort of superorganism. Aloi invited us to criticize our conceptions of “parasitic” plants since the term has many predatory and negative connotations that might not actually reflect the intentions to the plant itself. This brought me to questions like, if plants have morals, what kind of morals would they have?

Post 5: Politically Charged

3/18/25

We dove into several artist projects that show how plants can be politically charged due to their histories and ecologies. For this, we were shown five relevant projects:

Israel's Campaign To Destroy Life (2025) by Samaneh Moafi

Palestine Heirloom Seed Library by Vivien Sansour

Study for a Monument (2013-2016) by Abbas Akhavan

Revival Field (1991) by Mel Chin

Slow Cleanup (2008-2012) by Frances Whitehead

Post 4: Weeds

3/4/25

There exists a need to be more critical of what is deemed or marketed as “native” and “natural.” Because this judgment goes both ways, by labeling one thing as “native” and the other “foreign,” one is often depicted as healthy, positive, and desirable, while the other is not. This is often an inaccurate way to evaluate plants ecologically or for the purpose of this course, outside the anthropocentric lens. Especially with plants, it is limiting to label an entire species as simply “good” or “bad,” which the concept of nativity and biodiversity sometimes leads to. Sometimes this selectivity of what is considered “native” becomes a conversation of purist mentalities (this plant is good, so we eliminate the other ones). These notions are like that of human displacement and the concept of borders and belonging, they are politically charged. Three art pieces were mentioned to exemplify this criticism:

Weed Series (2022) by Jin Lee

Weeds by Mona Caron

Selected drawings by Zachary Logan

Final Project Update: I began this blog page for my final project today! I am trying to backtrack and get all my notes to reflect on each class and have begun a small amount of research on how charcoal is made.

Post 3: Vegetal Realism

2/18/25

Vegetal realism in artwork can cause reversal of the conventions that illustrate plants as passive, neutral, and object-like background fillers. Instead, it places importance on the portrayal of plants and removes a degree of anthropocentrism. This can be a politically potent decision especially in addressing topics such as immigration, minority representation, and exoticism, and critically reflecting upon the traditional “symbolic registers” of the purist Christian values that many representations of plants in fine art originate. By moving away from the symbolism that is far removed from the actual ecological and epistemological experiences of a plant, artists can use realism to depict truth in the individuality of plants. It is important to represent this individuality because plants are silent organisms living on such a different timeline than humans do. How we represent plants can shift traditions and revolutionize how we think of humanity and the world.

This class we delved into the history of plant representation in the fine art world from the 1850 realist movement of France to Edward Steicher’s Delphiniums in 1936, marking the first documented instance of bio art, and how that challenged the essence of fine art through an unsellable, unobtainable piece removed from the norms of modern consumerist culture. Anais Tondeur and her radioactive plant herbarium was mentioned, along with Anna Atkins’plant cyanotypes, Huangyong Ping’s controversial Theater of the World, Kira O’Reilly’s controversial In the wrong placeness performance, and O’Reilly’s Falling asleep with a pig reaction piece.

Final Project Update: This is also the week that we needed to choose a topic for the final project for this course. I decided to research my primary medium, charcoal and synthesize art pieces, literature, and accounts of artists creating their own charcoal to create a more plant-centric scope of the medium. I wanted to examine the connection between artists and the material world through plant matter and reflect on my own disconnection with the medium.

Post 2: Objectification & Symbolism

2/11/25

In art, objectification and symbolism play necessary roles as the act of making art will almost always involve the act of objectification. However, there is a threshold where objectification and symbolism become reductive and limit the way we think about certain topics. This is especially notable in artwork depicting plants. This lecture we began to cover the history of botanical documentation with figures such as Gherado Cibo and Luca Ghini cited as some of the first botanists doing field work with plants. Derived from the first documented manuscript depicting plants, the Beastiarium. This history lecture lead into a discussion of the inherent colonialism in naming and scientific “discovery.”

There is an interesting connection to figurative representation and the historical objectification that took place there, as established in the controversy of Manet’s Olympia. This was explained by the concept of a viewer’s gaze, that when unreturned by a nude subject, there is an implication of sensuality and objectification. Martha Nussbaum’s writing on Objectification (1995) was also discussed through the measures of instrumentality, authority denial, inertness, fungibility, violability, ownership, and denial of subjectivity. Another point of reference was Sexual Solipsism, essays by Rae Langton (2009). In relation to these measures, plants have been overtly objectified throughout the history of art with few exceptions, such as in the work of Lucien Freud.

The slow work of Freud, with his paintings taking upwards of a year to complete, often included plants in his composition. He worked realistically, with an emphasis on accuracy over beauty which caused his works to be deemed “ugly.” Yet through this ugliness, a sense of truth and a subtle lack of human versus animal versus botanical hierarchy among his subjects as his houseplants in the background were treated with the same sense of importance as the nude figures, showing a sense of flat ontology.

Other artists mentioned included: Rashid Johnson, Maggie Foskett, Henry Fox Talbot, Jeff Koons, and Damien Hurst. Aloi stressed that as artists, we have a responsibility to be more critical of the symbolic registers that have historically prevailed as they are often far removed from botanical accuracy and closer to upholding Christian values.

Post 1: Vegetative State (Estado Vegetal) by Manuela Infante

2/1/25

This performance piece by Infante was a rambling narrative weaving together characters’ perspectives of the same event: a young man crashes his motorcycle into a tree and due of the impact, enters a vegetative state. Unique to this performance is the character of the tree itself and the collective ecosystem it lives in beside the sidewalk. There is a poetic distinction between human and botanical characters: a repeated line echoes in my mind after watching this, “I can’t move.” Who cannot move? The tree? The young man?

The speculation on what the plants would say if they could speak to us in this situation are thought-provoking: “Tear open your floors, it’s not your house,” “We were here before you,” and my favorite, “When human beings are no long on the face of the earth, it will take plants only three months to cover everything.” The plants in this performance speak on the abuse to the environment humans have inflicted in a plant-first way: “imagine a forest of only pines, a town only of children,” and to the ecological neutrality of death and movement: “if you never die, then how can we say you’re alive?” or “the stiller something is, the more it survives.”

Bibliography

“Bahk Seon Ghi.” Art of the World Gallery, 2025, https://www.artoftheworldgallery.com/represented-artists/bahk-seon-ghi/.

Carey, Katie. “Artist Spotlight: The Expressive Lives of Tansy Lee Moir’s Trees.” Artwork Archive, 25 Apr. 2022, https://www.artworkarchive.com/blog/artist-spotlight-the-expressive-lives-of-tansy-lee-moir-s-trees.

“Charcoal.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1 May 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/drawing/charcoal.

“Charcoal — Art Mediums.” Obelisk Art History, 2022, https://www.arthistoryproject.com/mediums/charcoal/.

“Discover the Works of Gustavo Nazareno.” Opera Gallery – Modern and Contemporary Art, https://www.operagallery.com/artist/gustavo-nazareno.

Gulland, Sophie. “From Ancient Origins to Modern Artistry: Learning About Charcoal.” Eckersley’s Art & Craft, 4 Aug. 2023, https://www.eckersleys.com.au/inspiration/learning-about-charcoal/.

Kroeck, Kurt. “The History of Charcoal.” Nitram Art Inc., 6 Jan. 2014, https://nitramcharcoal.com/blogs/blog/history-charcoal.

Niklas, Karl. “Botany for the Next Millennium: Chapter I.” FDM Webseiten, https://www-archiv.fdm.uni-hamburg.de/b-online/ibc99/millenium/mil-chp1.html.

Rousar, Darren. Making Charcoal in a Charcoal Kiln. YouTube, 15 Sept. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uno0NmOEo7w.

Snipes, Susan. “I Made My Own Artist Charcoal.” Medium, 16 Oct. 2021, https://medium.com/@susansnipes/i-made-my-own-artist-charcoal-597342f2c6f7.